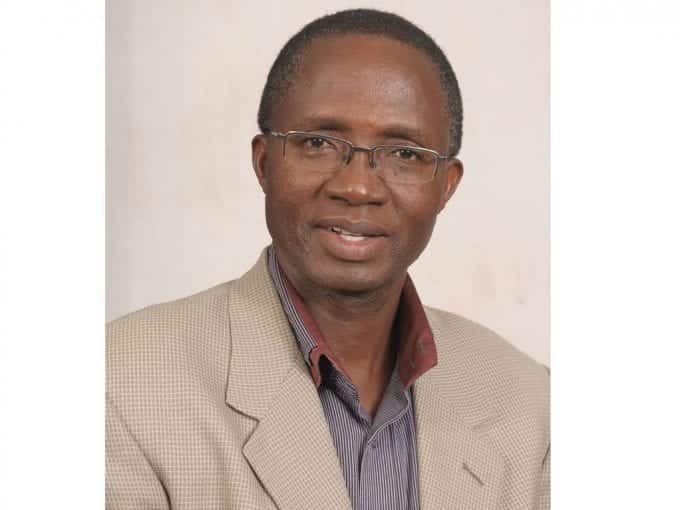

Kenyan scientist Kariuki Njenga is set to be inducted into the world’s most elite science bodies – the National Academy of Sciences in the United States — for his contribution to human medicine.

Kenyan scientist Kariuki Njenga is set to be inducted into the world’s most elite science bodies – the National Academy of Sciences in the United States — for his contribution to human medicine.

The professor of virology and global health at Washington State University and senior research officer at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (Kemri) is the second Kenyan, after anthropologist Maeve Leakey, to be admitted to the academy.

The Academy was created by an Act of Congress in 1863, and membership is considered one of the highest honours a scientist can receive.

There are currently 2,380 members, of whom 485 are foreign associates like Prof Njenga, and 190 have received Nobel prizes. The Academy’s directory shows only three other Africans, one each from Ethiopia, Nigeria and Ghana.

Every year, 6,000 scientists and members of the Academy convene for an annual meeting where they put their brains together to answer the world’s most pressing needs, from health, security and climate change, among other problems.

After this meeting, more than 250 reports are published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, to influence policy decisions and new research. It is at this meeting that members nominate and elect 80 members to the Academy. The candidates are vetted extensively, before a final ballot is cast.

Prof Njenga was 10 times less likely to be picked.

The number of scientists per million people in the developing world is 10 times less than that in developed countries, according to the Unesco Science Report. The US has 3,123 scientists for every million people, while Kenya has 318 researchers for every million.

CELEBRATION

When Prof Njenga was elected to the Academy, Washington State University erected banners in libraries and halls celebrating his nomination. In Kenya, the nomination passed without much notice.

Nevertheless, his four-decade career reveals a stellar curriculum vitae, with a focus on zoonotic diseases (which are passed from animals to humans).

He has just developed a system to respond to Rift Valley Fever. Between 2004 and 2010, while he was the head of laboratories at the regional Centres for Disease Control, Prof Njenga trained on the diagnosis of avian influenza for 14 regional laboratories in Africa, a role that he still holds to date, though he now focuses on disease detection.

Prof Njenga was instrumental in the establishment and the operation of the CDC lab from 2004 to 2010 — among the very first in the region with the equipment to conduct tests on haemorrhagic fevers like Ebola. He also trained a cohort of elite young scientists to track and respond to outbreaks in the Kenya Field Epidemiology and Lab Training Programme.

His career path shows the evolution of veterinary doctors in Kenya who, until recently, had been given the tag of “daktari wa ng’ombe (cattle doctor)”.

Now, it is acknowledged that vets are better equipped to handle zoonoses such as Rift Valley Fever, rabies and Ebola.

GRANTS

Kenya stopped hiring vets in the 1990s as part of the structural adjustment programmes and privatisation of veterinary services, leaving most of them to venture into research on zoonoses.

Prof Njenga, who relies on grants for his work, wishes that the government would invest more money in research, not just as a solution to people’s problems, but as an economic gain through the generation of innovations.

His peers describe him as proud, demanding and a traitor to the “true veterinary medicine,” which is dedicated to animal health.

But he makes no apologies for it: “I have never and will never supervise someone whose research does not touch on human health. I want to know how a disease wiping out a brood of chicken in Siaya affects a mother’s capability to feed her children,” he says.

Brought up in Kitale, Prof Njenga earned his undergraduate and master’s degrees in veterinary medicine at the University of Nairobi, before heading out to the Penn State University in the US for his PhD.

He completed his post-doctoral fellowship at the Mayo Clinic and Foundation. Njenga then worked hard to become a professor and get tenure — permanent and pensionable in Kenyan terms — and after it was awarded, he went into depression.

“I would go to the office and just stare into the computer and ask, ‘Is this it? Is this all what I worked for?’” Now he is happy that his peers have recognised his work, in what he calls the “highest achievement” of his career.

-nation.co.ke