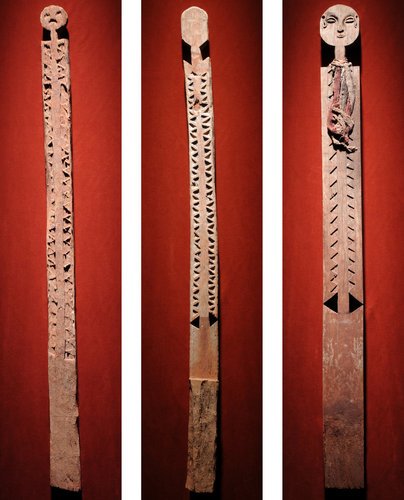

Three of the 30 totems, or vigango, that the Denver Museum of Nature and Science is handing over to the National Museums of Kenya.

The paleontologist Richard Leakey has called their removal a “sacrilege.” Kenyan villagers have said their theft led to crop failure and ailing livestock. It is little wonder, then, that the long, slender wooden East African memorial totems known as vigango are creating a spiritual crisis of sorts for American museums. Many want to return them, but are not finding that so easy.

Now, the Denver Museum of Nature and Science says it has devised a way to return the 30 vigango it received as donations in 1990 from two Hollywood collectors, the actor Gene Hackman and the film producer Art Linson. The approach, museum officials say, balances the institution’s need to safeguard its collection and meet its fiduciary duties to benefactors and the public with the growing imperative to give sanctified objects back to tribal people.

“The process is often complicated, expensive and never straightforward,” said Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh, the museum’s curator of anthropology. “But just because a museum is not legally required to return cultural property does not mean it lacks an ethical obligation to do so.”

The museum this month will deliver its 30 vigango (pronounced vee-GON-go; the singular form is kigango) to the National Museums of Kenya. Officials there will choose whether to display the objects, hunt through the nation’s hinterlands for their true owners and original sites, or allow them to decay slowly and ceremoniously, as was intended by their consecrators. Whatever they opt to do, Kenyan officials say, sovereignty over the objects should be theirs and not in the hands of foreign museums. (The details of the transfer are still being negotiated.)

Some 20 institutions in the United States own about 400 of the totems, according to Monica L. Udvardy, a professor of anthropology at the University of Kentucky and an expert on Kenyan culture who has studied and tracked vigango for 30 years. She said that Kenyans believe that vigango are invested with divine powers and should never have been removed from their sites and treated as global art commodities. Kenyan officials have made constant pleas to have the objects sent back.

But repatriating them takes far more than addressing a parcel. No federal or international laws prevent Americans from owning the totems, while Kenyan law does not forbid their sale. And the Kenyan government says that finding which village or family consecrated a specific kigango is arduous, given that many were taken more than 30 years ago and that agricultural smallholders in Kenya are often nomadic.

A result is that museum trustees seeking legally to relinquish, or deaccession, their vigango have no rightful owners to hand them to.

Vigango are carved from a termite-resistant wood by members of the Mijikenda people of Kenya and erected to commemorate relatives and important village headmen. Notched and round-headed, they vary in length from four to nine feet and are dressed, served food and tended as living icons. Hundreds of vigango were bought or donated to museums in the 1980s and 1990s by collectors of African art, including some Hollywood luminaries.

Stephen E. Nash, chairman of the anthropology department at the Denver museum, said his institution’s decision to give the objects to the Kenyan government museum could offer guidance to other museums that agree that vigango are spiritual and cultural property, but feel stymied by institutional barriers to giving up objects, or because they cannot return them directly to their rightful families. Increasing publicity about tribal objects with a spiritual significance, including Native American artifacts like Hopi and Apache ceremonial items recently auctioned in Paris, has given a fresh impetus to the repatriation movement.

Maxwell L. Anderson, director of the Dallas Museum of Art and chairman of an Association of Art Museum Directors task force on archaeological and ancient artifacts, said institutions should evaluate restitution claims case by case, with an eye toward returning objects.

“Irrefutable evidence of looting or illegal export from a source country is often hard to provide,” Mr. Anderson said in an email. “But there is often strong circumstantial evidence that compels museum directors to advocate deaccessioning, even at the risk of alienating donors.”

To date, only two vigango have been returned by American museums, one each by the Illinois State University Museum in Springfield and the Hampton University Museum in Virginia. Their decisions were based on the work of Ms. Udvardy, who in 1985 photographed a resident of a village called Kakwakwani standing next to twin vigango in their original site.

Years later, she recognized one of the totems in a slide from the Illinois museum. After that, Ms. Udvardy scoured museum catalogs and photo collections to find other matches. The Illinois museum still has about 38 vigango, while the Hampton museum holds nearly 100.

This glacial rate of repatriation has long frustrated Ms. Udvardy, who was contacted by Mr. Colwell-Chanthaphonh at the Denver museum for advice in 2008. Even then, it took the museum five years to negotiate the repatriation.

Ms. Udvardy and Mr. Colwell-Chanthaphonh discovered in their research that the 30 vigango had been donated by Mr. Hackman and Mr. Linson, who were both clients of the United States’ foremost dealer in vigango and other East African artifacts, Ernie Wolfe IIIof Los Angeles. A brash, boar-hunting devotee of Africa, Mr. Wolfe has long acknowledged that he was a pivotal figure in making a market for vigango in the United States. He said in a telephone interview that the objects became popular in Hollywood in the 1980s. Along with Mr. Hackman and Mr. Linson, aficionados have included the actors Powers Boothe, Linda Evans and Shelley Hack.

Mr. Wolfe stoutly defends collecting, selling and exhibiting the objects, saying he rescued them after they had spent their spiritual powers — been “deactivated,” as he puts it — and had been abandoned by their consecrators. He also said that Kenyan officials applauded his first presentation of vigango in the United States, at the Smithsonian Institution in 1979.

Mr. Wolfe said vigango sold for perhaps $1,500 apiece in the 1980s. Mr. Colwell-Chanthaphonh said they are now valued at upward of $5,000 and that one fetched $9,500 at auction in Paris in 2012.

The Denver Museum “passionately values” such objects, Mr. Colwell-Chanthaphonh said, but added, “Collections should not come at the price of a source community’s dignity and well-being.”

Source-nytimes.com

Denver Museum to Return Stolen Totems to Kenyan Museum