It began with a suicide blast at the gates of the African Union’s AMISOM base outside the southern Somali town of el-Ade.

A fierce battle ensued, at the end of which some 60 Kenyan troops were dead; some of their bodies had been reportedly dragged through the town and al-Shabaab left with stockpiles of captured weapons, ammunition and some 28 vehicles.

That much is widely reported.

Explaining the attack journalists have pointed to:

- the recent setbacks al-Shabaab have suffered and their loss of the port of Kismayo,

- a meeting of Somali politicians to discuss elections scheduled for later this year,

- the recent splits inside and defections from al-Shabaab over whether to remain affiliated to al-Qaeda or to shit allegiance to ISIS or ‘Islamic State’.

These factors led to the raid by an estimated 200 militants belonging to Saleh Nabhany Brigade, named after a Kenyan Al Qaeda field operative killed in 2009 by the US drone.

Looking a little deeper…the establishmen of Jubaland

The Kenyan base lies in Jubaland – a buffer state created by the Kenyans along their northern border to protect the country from the ravages of Somalia’s civil war and Islamic movements.

Somalia was forced to recognise Jubaland in September 2013 after nine days of arm-twisting.

The entire sorry saga was witnessed by Nicholas Kay, the UN’s Special Representative in Somalia; welcomed by Catherine Ashton for the European Union and supported by the African Union. Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, the South African chair of African Union described the agreement as “historic”, declaring that it was “a further illustration of the capacity of the Somalis to triumph over their differences.”

Kenyan ambitions – US warnings

The Kenyan foreign ministry has long seen the establishment of a buffer state along its northern border as vital to its security interests.

Thanks to Wikileaks, we know that Kenya’s Foreign Minister, Moses Wetangula, practically begged the United States for its support when he saw Johnnie Carsons, President Obama’s most senior US Africa official, in January 2010.

The Kenyans were requesting backing for an invasion of Somalia to create Jubaland, but the Americans were far from keen.

As the confidential embassy telex puts it: “Carson tactfully, but categorically refused the Kenyan delegation’s attempts to enlist US Government support for their effort.” It was, said the telex, the third time Wetangula had made the appeal, but Carsons resisted, pointing out – rightly – that “the initiative could backfire.”

Critically, Carsons warned that: “if successful, a Lower Juba entity could emerge as a rival to the TFG” (Somalia’s Transitional Federal Government).

This is exactly what came about.

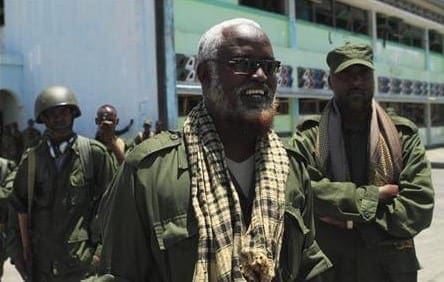

Enter Sheikh Madobe

The deal officially recognises Ahmed Mohamed Islam (known, like all Somalis by a nickname – ‘Madobe’) as the ‘leader’ of Jubaland. Yet only a month earlier Sheikh Madobe was described in a major UN report as a “spoiler” and one of the chief threats to Somali stability.

The Sheikh was said to be “subverting the efforts of the Federal Government leadership and its partners to extend the reach of Government authority and stabilise the country, particularly in Kismaayo.”

What the Baroness Ashton and her colleagues have done is anoint a man who has been roundly denounced by the Monitoring Group, established by the UN Security Council. Its July report pointed out that the Sheikh had been a member of the short-lived Union of Islamic Courts, which was ousted by Ethiopia during its 2006 invasion of Somalia.

What happened next is interesting.

As the report puts it: “Madobe’s forces returned to Kismayo in August 2008, when Al-Shabaab and Hizbul Islam recaptured the city following the withdrawal of Ethiopian troops from Somalia.” At this time the Sheikh Madobe was a key player in the al-Qaeda linked network.

But, as is ever the case in Somalia, clan and inter-clan rivalry came into play and the Sheikh fell out with his former allies. He threw in his lot with the African peacekeepers and the Federal Government.

Sheikh Madobe did not cut his ties with al-Sabaab altogether and the UN report accuses him of continuing the export of charcoal from territory controlled by the Islamists – a trade long since outlawed by the UN because of its catastrophic impact on the Somali environment.

The roles of Kenya and Ethiopia

The outcome has been a triumph for Somalia’s neighbours, even though Kenya and Ethiopia will continue to vie for influence in this critical part of the country.

Brushing aside American concerns aside, Kenya sent its troops into Somalia in October 2011. As predicted, they found it very heavy going and it was to take almost a year before al-Shabaab were driven from Kismaayo.

For the Ethiopians, the establishment of Jubaland is a further fragmentation of Somalia, its sworn enemy since the Somalis invaded their country in 1977. It was an attack that is imprinted on Ethiopian memories, fuelling a determination to see the end of a powerful, centralised Somali state.

Sheikh Madobe continues to be Ethiopia’s man in the region, and was warmly welcomed during a visit in December 2015.

Charcoal, shisha pipes, Saudi Arabia and the UAE

Behind this tale of international intrigue and terrorism lies a story of ecological devastation.

For decades this area of southern Somalia has provided the Saudis and other Arabs of the Arabian peninsula withcharcoal for their shisha pipes. Vast quantities are shipped out annually – devastating the forests of the region, which are now seriously depleted.

According to one official study over 4.3 million trees were cut down in one year.

Al-Shabaab used to make serious sums of money from these exports, and for a while Sheikh Madobe is accused of sharing these revenues with them. But – according to the UN – in 2015 he ended this arrangement.

This is what the report says:

“Evidence collected by the Monitoring Group, however, suggests that the ties between those controlling the trade in Kismayo and elements of Al-Shabaab in Lower and Middle Jubba have been strained over the past year. In January 2015, senior Al-Shabaab officials are reported to have called for the closure of charcoal production sites in Lower and Middle Jubba. In the following months, charcoal producers were arrested by the group, and many of those found carrying charcoal along the major supply routes were executed and their vehicles burned along with their cargo. During that period, suppliers were forced to use smaller minibus-type vehicles and back roads to avoid detection by Al-Shabaab on the major supply routes. Unconfirmed reports indicate that an agreement on the distribution of taxation collected from charcoal at the export sites fell apart when Ahmed “Madobe” withheld Al-Shabaab’s shares of export proceeds early in 2015 in preparation for the formation of the Jubba Regional Assembly in April and May 2015. The withholding of funds due to Al-Shabaab prompted the blockade on charcoal to the city, which may also partly explain the significant expansion of operations in Buur Gaabo.”

And the UN goes on to accuse Jubaland and the African Union force of profiteering from the charcoal trade.

“While the Monitoring Group has received some support from the Federal Government of Somalia in its investigations into the charcoal trade in southern Somalia, no apparent efforts have been made by either the Interim Jubba Administration or local contingents of AMISOM to implement or report on the ban, supporting the Group’s assertion that both continue to be actively engaged in and profiting from the trade….”

When I drew attention to this last night, it was confirmed by a Somali who tweeted this:

Conclusion

The Kenyan troops who are caught up in this complex web of greed, international politics and regional rivalries have paid with their lives. More than sixty of them are now dead and al-Shabaab is once more well armed and dangerous.

It is a sorry tale indeed.