In its first week of operations along the M Street NW corridor, Swahili Village had gangbuster sales.

In its second week, the Kenyan restaurant was closing its doors.

The reverberations of the novel coronavirus has devastated the entire restaurant industry. But for the brand new African fine dining restaurant, things have been particularly difficult.

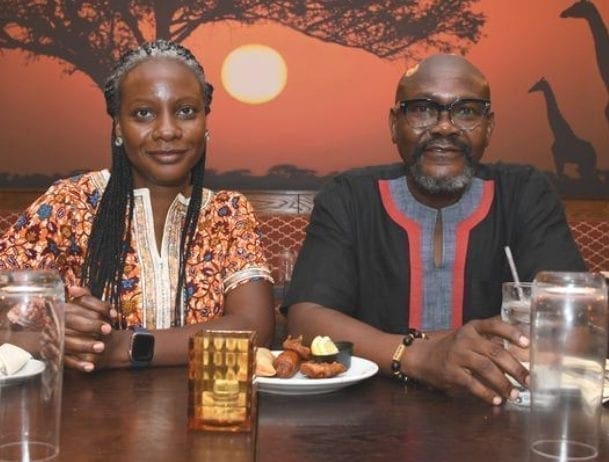

Owners Kevin and Lynn Onyona, a husband-and-wife team, had thought of everything. They invested roughly $1.3 million into their second space at 1990 M St. NW. They hired and meticulously trained 65 employees for their March 5 opening. They had their eye on clientele from the World Bank, situated just a few blocks from their new awning, and a grand public launch on the books for April 10.

JOANNE S. LAWTON

But suddenly folks stopped coming. Employees began working from home. And before they could even get their new restaurant situated, the entire food and beverage industry essentially shut down March 16 as decreed by the Bowser administration, forcing new challenges upon the couple they could have never foreseen.

“There was a huge demand for us to get into downtown D.C., which was something our customers showed us — there’s potential for us to do very well there,” says Kevin Onyona, who opened the first location in College Park in 2009 before moving to Beltsville in 2016. “The diplomatic community, the [International Finance Corp.], the World Bank, the State Department all gave us the indication it was time for us to actually go ahead and invest in downtown D.C.”

Unlike other restaurants in the region, Swahili Village hadn’t yet had the chance to build up the loyal customer base in downtown D.C. to sustain takeout or delivery business for long. After two weeks of offering it, the restaurant fully closed its doors March 30. The Onyonas used their remaining inventory to prepare 450 meals for first responders to the coronavirus pandemic. And in the time since, the restaurant has had to lay off all 61 of its new — and newly trained — D.C. employees.

To add to their troubles, Kevin says the restaurant might not qualify for a small business loan under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act that Congress recently passed to help those facing economic damage due to fallout of COVID-19’s spread. After all, its Swahili Village location in the District wasn’t in operation before Feb. 15, a tenure the stimulus legislation stipulates in order to receive aid.

“In every way, people like us are really in dire trouble,” Kevin says. “We find ourselves completely flat on our feet.”

On the plus side, Kevin says he and his wife have been in talks with their landlord, Meitnerium Alpha LLC, which has been working with them regarding their rent bill, which tops $20,000 for the 6,771-square-foot restaurant.

Through the tribulations, they hold fast to one belief: They will be able to reopen when the pandemic passes.

“We’re taking it one day at a time,” Kevin says. “We should be able to be back up and running again. After all this, you must have the faith and tenacity to believe that the reason why you did this was a good reason.”

By Katishi Maake

Source-bizjournals.com

Swahili Village: Built by a Village, Closed by a Virus

Swahili Village: Built by a Village, Closed by a Virus