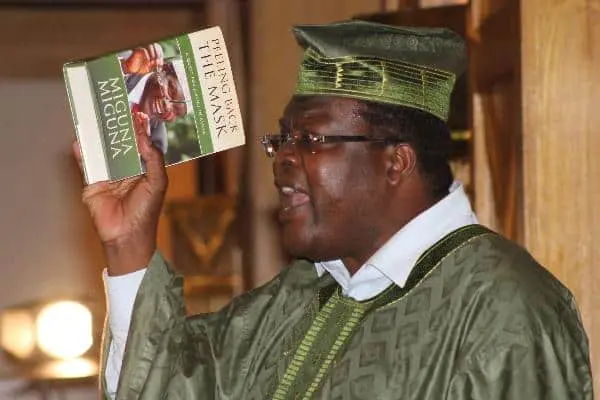

The reception of Miguna Miguna’s political memoir reflected three key things about our political culture. First, a tendency towards absolute intolerance to divergent views. Second, the use of ethnicity as a unit of literary analysis.

Third, our readerly habits, which are largely elliptical and second-hand — skipping large portions of the text and relying exclusively on what others have said about a text to form an opinion on it.

There were full-fledged combative riots at launches of Miguna’s book, but no full-fledged reviews of the book to suggest that some people actually read it from cover to cover! Commentators in the press and on broadcasting benches were united by one thing: none of them had read the book in its entirety.

If they had read the whole text — rather than scanned the selective serialisation in the press or listened to Miguna at various interviews — we would not have heard so much aimless speculation about the identity of the facilitators of this book project!

The answer to that question is on page 562 under Acknowledgements.

Shallow debates

There is nothing new or peculiar in these shallow debates on Peeling Back the Mask. In the two decades that I taught Literature at Moi University, I experienced one rather depressing thing — very many literate Kenyans (even the ones studying Literature!) are absolutely averse to reading anything that runs over 50 pages.

They prefer to skim through what others have said about the text than to learn first-hand from the text. The comments sections of our online dailies are the peak of this ultra-Kenyan form of criticism — making a comment on preceding comments very often without any reference to the issues raised in the article or the news item under discussion.

Another enduring practice in Kenyan criticism is ad hominem engagement that reminds me of high school sports in my day and the dubious advice that hockey coaches sometimes gave to irredeemably weak teams — if you can’t get the ball, get the opponents’ ankles or shins.

In Kenya’s culture of passive-aggressive criticism, this unprofessional practice of hitting the player rather than the ball is manifested in vicious attacks of the author based on perceived personal traits and in ways that totally shut out the original argument.

It reduces the debate to a hateful personal attack shaped by three main assumptions: ethnic identity, political affiliation and economic status.

Any honest critic of Peeling Back the Mask should start by commending Miguna for having the dogged discipline to sit down and write.

Writing of this kind is both a lonely and a humbling exercise and few able and (intellectually) endowed Kenyans have had the discipline to contribute to the nation’s history by telling us their stories.

It takes nothing short of military discipline for one to (walk away from the idle chatter in Nairobi’s bars and coffeehouses), sit still before a blank page and dare to fill it up with cogent thoughts that bare one’s soul and intellect.

And in the cycle of appointments to and dismissal from high office, very few Kenyans have had the mental fortitude to stare down our blood-thirsty media and turn their misfortune into an opportunity.

We must salute Miguna’s courage in refusing to feel useless or to wallow in self-pity at a time when his whole world appeared to be crumbling at his feet.

However, Miguna’s contribution to our nation’s history suffers from some critical errors in the rendering of that past. He tells us that the Constitution was “amended in 1983 to make Kenya a de jure one party state” (p.52). The Constitution was actually amended in 1981.

Miguna rightly depicts the University of Nairobi in the mid 1980s as an institution that danced to the whims of the Moi Government. But he stretches this argument unduly when he lists books that were banned in those years including those by Ngugi wa Thiong’o ( p56).

I was a post-graduate student of Literature at the University of Nairobi when Miguna was an undergraduate so I know that he is wrong about the banning of Ngugi’s books not just because I regularly bought them at the university bookshop, but because my lecturers taught them in class and I wrote copious term essays and examination answers on Ngugi. I studied A Grain of Wheat for my A levels.

Dr. Eddah Gachukia taught me The River Between and The Black Hermit in the first year of my undergraduate.

Decolonizing the Mind, Devil on the Cross and Petals of Blood were core reading in my MA ‘Criticism of African Fiction’ course and I have a vivid memory of buying Detained, Moving the Centre and Matigari from Prestige Bookshop on Mama Ngina Street. So when were Ngugi’s books banned? From where? By whom? Is anyone in possession of the Gazette Notice that stipulated this ban?

I have detailed my prescribed engagement with Ngugi’s work in high school and throughout my years at the University of Nairobi to support my argument that Miguna’s word is not gospel.

Using the doctrine of logical assumptions, we can conclude that if this aspect of Miguna’s account of the Moi years is incorrect, there are likely to be other errors in his rendering of the Kibaki and the nusu mkateyears — a tendency to paint Government as unduly brutal, backward and interfering, the economy as hopeless beyond redemption.

It is the psyche of the African exile that Ike Oguine defines in A Squatter’s Tale, a need to continually justify one’s absence from the motherland.

While one might account for Miguna’s tendency to expect the worst from successive Kenyan governments, there is no excuse for his failure to get right fundamental facts about who served in government when.

Errors of this kind make some of his claims simply ridiculous. For instance, on pp.145-6 he argues that the reason Kikuyus and Kisiis constituted “more than 60 percent of the Kenyan diaspora community in the early 1990s was because “up to that point, only Gikuyus and Kisiis had served as ministers of Finance… it is conceivable that those ministers were only assisting members of their ethnic communities to get scholarships or obtain the necessary foreign exchange to travel abroad.”

Musalia Mudavadi, a Luhya, was Finance minister in 1993 before Simeon Nyachae, a Kisii, was appointed to the ministry in 1997. And Simeon Nyachae’s son, Charles, has never served as a Cabinet minister as Miguna states on p.156.

Rather shifty

Miguna’s account of the chronology of the election-related violence of 2007/2008 is rather shifty. He forgets that in the Rift Valley, forced evictions started as early as September 2007 in Kuresoi constituency.

He omits to mention that on the eve of the elections, a young man wearing a PNU T-shirt was killed by a mob in Kibera. Miguna does not seem to recall the killing of Administration Policemen in Nyanza on December, 26 2007.

His outrage over the shooting of “thousands of Luo youth” in Kisumu and Nairobi washes out the story of the thousands of Kikuyu and Kisii peasants mercilessly killed in Uasin Gishu, Trans Nzoia, Kericho and Nandi in the four weeks of January 2008 BEFORE Mungiki’s brutal revenge attacks in Naivasha on Sunday 27 January, 2008.

Miguna’s fury with the violence of the security forces is palpable and repeatedly expressed. These emotions are absent in his account of the burning of women and children in the Kiambaa church near Eldoret on New Year’s Day 2008. Miguna mentions it in a bland and fleeting tone devoid of indignation or compassion.

So this is not a matter of outrage at wanton destruction of human lives but of which human lives. Those of suspected PNU sympathisers command no raised tone of voice, no persistent and repeated mention and fury.

And this coming from an indefatigable human rights defender, a vocal advocate of individual rights who tells us later in the story (p.559) that he has “never subscribed to the belief that all struggles need martyrs”!

And in documenting the fall-out after the announcement of the presidential election, nowhere does Miguna, the master of broadcasting injustice, proffer an opinion on the tortured land question and cycle of dispossession that was tied to ODM’s demands over a stolen election and used to justify the horrors in the Rift Valley.

The slant on this chronology of post election violence and Miguna’s guarded reference to Raila refusing to join his troops at the frontline of the battle, of Raila carelessly holding numerous uncensored conversations on his cell phone at the height of the conflict suggests that Miguna knows a whole lot more about the violence of 2007/2008 than he is willing to say.