As Kenya and Zimbabwe navigate their political futures, much in both countries will no doubt change – one hopes for the better. In any case, their ties with China will be an important metric in assessing their trajectory, and here Zimbabwe may have the advantage.

BEIJING – Ask anyone with a basic knowledge of Africa which country is more poised for success – Zimbabwe or Kenya – and he or she will undoubtedly answer “Kenya.” Events of the last week would seem to confirm that verdict.

Nov 24, 2017 JEFFREY FRANKELwarns that Republicans’ proposed tax legislation will blow up the US budget deficit – again.

On Monday, after Kenya’s Supreme Court upheld the reelection of President Uhuru Kenyatta in the country’s contested presidential election, the rule of law seemed to trump political violence for the first time in years. Zimbabwe, on the other hand, is without President Robert Mugabe for the first time in 37 years. And, although the country may be ecstatic now, its political future is far from certain.

But as a Kenyan living in China, one of the African continent’s most important development partners, I see one metric that tips the scale in Zimbabwe’s favor: its relationship with my adopted home. In fact, Zimbabwe’s economic and political ties to China could prove decisive for Africa’s perpetual underdog.

On paper, Kenya clearly has the edge. Although Zimbabwe has more natural resources and mineral wealth, it has far less land and extreme poverty is much more widespread. More than 70% of the country’s 16 million people live on less than $1.90 a day, compared to 46% of Kenya’s 48 million people. Moreover, as many as 90% of Zimbabweans are unemployed or underemployed, compared to 39% of Kenyans.

Even Kenya’s economic links to China might seem more impressive at first glance. Kenya and China have long cooperated on large infrastructure projects. A Chinese-funded railway between Nairobi and Mombasa, which opened earlier this year, is the latest example. Since 2000, China has offered Kenya $6.8 billion in loans for infrastructure projects, compared to $1.7 billion for Zimbabwe. And, because loan conditions often include a requirement to hire Chinese employees, Kenya had more than 7,400 at the end of 2015, while Zimbabwe had just over 950.

But in the competition for Chinese largesse, Kenya’s advantage over Zimbabwe ends there. Cumulative Chinese foreign direct investment since 2003 has reached nearly $7 billion in Zimbabwe, compared to $3.9 billion for Kenya. Year on year, more Chinese money is flowing to Zimbabwe as well.

Moreover, Zimbabwe’s trade balance with China is far superior to Kenya’s. In 2015, Kenya’s exports to China totaled $99 million, while it imported from China a staggering 60 times that amount. Even taking into account imports of materials tied to Chinese-built infrastructure, this is an exceptionally wide bilateral deficit.

Zimbabwe, on the other hand, despite its slow growth rate, exported $766 million worth of goods to China in 2015, and imported $546 million. Most surprisingly, Zimbabwe’s exports were not restricted to minerals and metals, as one might assume, but also included tobacco and cotton, products that are relatively more labor-intensive, meaning more job creation at home. And, while Zimbabwe has around 50 fewer registered Chinese companies than Kenya, Kenya’s economy is around 4.5 times the size of Zimbabwe’s, clearly implying that those firms that are operating there contribute more to the country’s economy.

How has Zimbabwe achieved what looks like, at least from a numerical perspective, a more productive relationship with China than Kenya has?

Few beyond Mugabe and his close colleagues, including the country’s new president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, know for sure. But one way to make an educated guess is to compare both countries’ history of bilateral engagement with China.

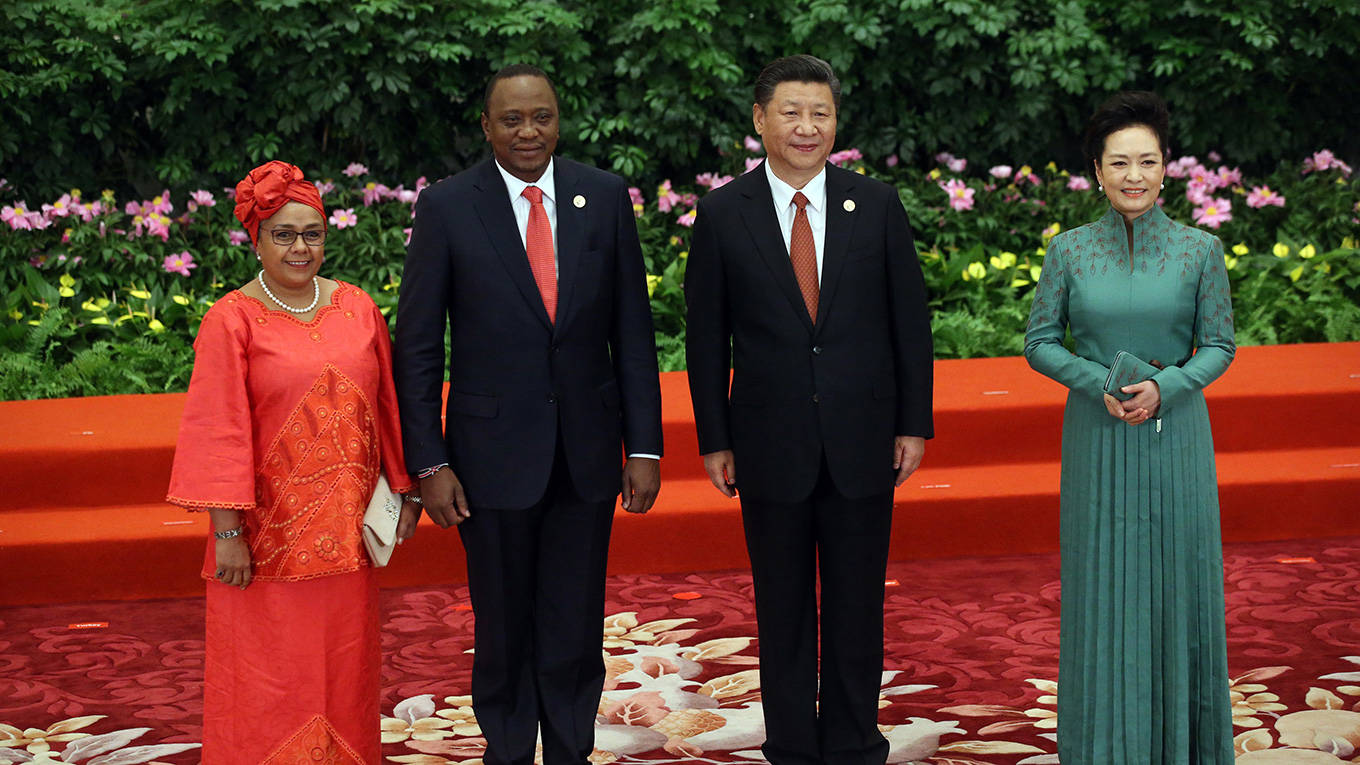

Both Kenya and Zimbabwe have had two visits from Chinese heads of state during their post-colonial histories. Chinese President Jiang Zemin visited each country in 1996, while President Hu Jintao visited Kenya in 2006. China’s current president, Xi Jinping, visited Zimbabwe in 2015.

State visits in the other direction have been more uneven. Mugabe’s first visit to China was in 1980, just six months after independence; he made 13 more during his tenure, and high-level visits by other Zimbabwean officials were even more frequent, occurring roughly once every two years during Mugabe’s reign. Kenyan presidents, by contrast, traveled to China just six times during the same period, most recently in May 2017.

Zimbabwe’s leaders made the most of their visits to press for trade and military cooperation, and likely engaged directly with private Chinese companies. This has nurtured a culture of reciprocity. Just a few months ago, for example, a Chinese company approached my firm asking for advice about how to enter Zimbabwe’s health-care market. I have not yet fielded similar questions about gaining access to markets in Kenya.

China’s role in African economies has been criticized; but, as I have argued before, Chinese investment has also been a lifeline to many on the continent. From creating employment opportunities to providing direct investment in infrastructure, China has been a partner to Africa when many Western investors preferred to stay away.

How Kenya and Zimbabwe navigate their future relationships with China remains to be seen. Both countries have supported Xi’s signature Belt and Road Initiative, which, in theory, should increase their strategic value to China. Kenya’s return to political stability should also sustain, if not deepen, the country’s economic engagement with China.

Zimbabwe’s historic ties to China will be no less important. Following Mugabe’s resignation, China’s foreign ministry went out of its way to praise the “friendship between China and Zimbabwe,” and Mnangagwa can be expected to continue that relationship. The new president received military training in China, and paid an official visit as speaker of the parliament in 2001. There is even speculation that China was warned of the looming coup in Zimbabwe, if not consulted beforehand.

As Kenya and Zimbabwe navigate their political futures, much in both countries will no doubt change – one hopes for the better. Their ties with China will be a key metric in assessing their trajectory.

-project-syndicate.org