A Seattle-based nonprofit is helping save lives in Kenya and elsewhere with highly realistic training sessions that prepare health-care workers to manage a childbirth emergency.

NAIROBI, Kenya — “How is my baby? I can’t hear him crying,” the mother pleads with the midwife as the pool of blood spills over the hospital bed, splashing onto the stained tile floor.

The blood is fake and the baby is plastic. It’s a training session. But the young Kenyan health worker is all professionalism.

“Your baby is doing fine,” he says, while fervently pumping the neonatal resuscitation bag. The new mother pretends to lose consciousness before she can hear the first cries from her newborn.

The stress lingering in the delivery room isn’t unfamiliar for the dozen nurses and midwives who now crowd around the bed, estimating the amount of blood lost. They are used to working in a crisis setting.

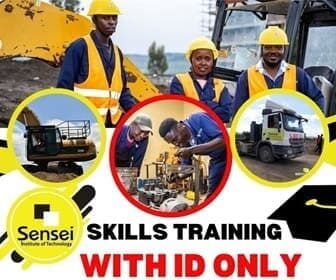

The health-care workers are at Nairobi’s Mbagathi District Hospital, taking part in an emergency obstetrics training simulation run by PRONTO International, a Seattle-based organization that is partnered with the University of Washington.

The blood may be fake, but the consequences are real. Many of the midwives at the training session work in severely understaffed facilities overrun with pregnant mothers. And they lack essential supplies like gloves and bulb syringes.

PRONTO’s low-cost, highly realistic birth-simulation trainings help health workers save the lives of mothers and babies despite huge challenges. And those challenges are not unique to Kenya. Poor-quality health systems can be deadly for new mothers.

Throughout their lifetime, women in sub-Saharan Africa have a 1 in 38 chance of dying from complications from pregnancy or childbirth. In developed countries, it’s 1 in 3,700.

Maternal health and childbirth interventions rarely get the publicity of exciting technological innovations in global health. Investments in health systems just don’t attract attention like the rush to create an Ebola vaccine or the chance to watch Bill Gates drink a glass of water converted from feces by a $1.5 million machine.

What they lack in attention, these low-cost interventions make up for with results. Simply improving the quality of care given during births that already take place in health facilities around the world would save 2 million lives each year, according to a research series in The Lancet.

PRONTO International started in 2008 as a partnership with the government of Mexico to reduce maternal mortality. The country had increased the percentage of births occurring in health facilities, but poor-quality care prevented any real improvements in maternal-health outcomes. In response, Dr. Dilys Walker, then working at the National Institute of Public Health of Mexico, led a team that developed simulation trainings based on emergency obstetric scenarios.

Care improved dramatically. The intervention hospitals had a 40 percent reduction in hospital-based neonatal mortality and more than 20 percent fewer cesarean sections.

PRONTO has since trained more than 2,400 health workers in six countries. The organization has received support and funding from several key players in global health including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, World Health Organization and USAID.

In 2012, PRONTO joined with the University of Nairobi, the Kenyan Ministry of Health and others to provide simulation trainings for government health workers.

It was a critical time. Just a year later, President Uhuru Kenyatta, making good on a landmark campaign promise, declared that government facilities would provide free maternity care. In a country where new mothers were frequently detained in hospitals for weeks until their friends and family could scrounge up enough money to pay off medical bills, the impact was immediate.

But the new policy brought new headaches for overburdened hospitals. Births at one of Nairobi’s major hospitals, Mama Lucy Kibaki, initially jumped from 400 to 900 a month, according to Dr. Richard Bor, the facility’s only obstetrician.

On most shifts, the number of midwives on duty ranges from one to three. They can hardly keep up with the 25 to 30 deliveries each day. The hospital simply wasn’t prepared for such a massive influx of patients. Quality suffered and women started avoiding the maternity ward, bringing the number of births down to 700 per month.

“I don’t think we met the expectations,” explains Dr. Bor. “There were too many women delivering, too few health workers, and the place was crowded. … Did you know there are not enough beds? There are women sitting outside, laboring on a [wooden] bench.”

Source-seattletimes.com