Homeless Diaspora: Dark Secrets of Kenyans in the US

“There was one shower, for the entire floor. There were bedbugs. There were rats. People come from the streets with all sorts of things, you know. It was difficult. It was very difficult,” so begins my conversation with Moses Munene, who was homeless in Washington DC.

Yet that’s not what comes to mind when you speak to Moses Munene, now a property developer in Kenya.

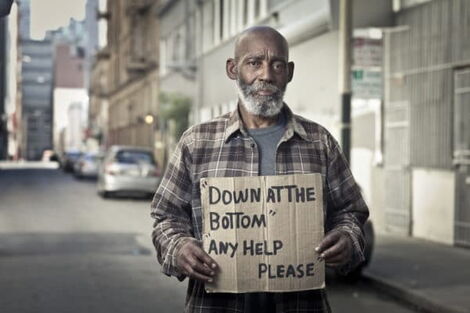

As he narrates his tale with charming candour it is difficult to lump the arresting personality with an image of those who bear the tag ‘homeless’.

But for one and a half years, Munene was indeed homeless in Washington DC, the capital of the United States, the land of opportunity, or so it has been termed.

A Kenyan by birth, he travelled to the US in 2002, seeking medical treatment after a bad fall injured his spine, he was 36 then.

“Once I got to DC, I stayed with one guy for two to three days, who then took me to a Christian place where I could live but they wouldn’t take me in. I called the Kenyan embassy then but they didn’t have any options, so I slept out in the cold that night.”

Perhaps it was a foreshadowing of things to come but Munene could not have known this then. After two nights in the cold, a lady from the Kenyan embassy referred him to Christ House.

“I was taken in by a medical facility for the homeless, Christ House. They arranged everything from my medical insurance to planning for my surgery.

“I stayed there for around six months but they could only host me for the duration of my treatment. Once that ended, they had no choice but to take me to a shelter.”

This was the turn of the road where Munene, a man of great faith as is evident from the references he splices in throughout our conversation, began his solitary sojourn into the world of homelessness.

“It was hard. In the shelter, once you wake up in the morning you leave so they can clean. So I used to go to hotels where meetings were held. I’d spend my whole day there, sometimes I’d get lunch if they were serving it and come back to the shelter in the evening.”

Pulling from his wealth of memories, Munene paints me a picture of the shape that life took while he lived at the shelter.

“Everyone has their own bed where you put your suitcase, sometimes it gets really cold and you don’t want to leave. People would smoke in the shelter so when you came in you’d find everyone smoking everywhere.”

Munene explained that the shelter had a six-month policy. Once you exhausted your months, you’d have to go back to the streets. Yet, with the industrious spirit of the motherland colouring his bones, the Kenyan got a job as a desk monitor and was able to extend his stay for another six months.

I asked Munene how his family allowed him to live in a shelter in a foreign country, yet he had a house waiting for him in Kenya.

“My family didn’t know I was in the shelter, I lied. I told them I was in college because once you are here people expect you to have a certain kind of income.”

For every hill, a valley and Munene eventually emerged into the light when his troubles made it to the ears of Kenyans in the diaspora.

“When Kenyans in Washington found out that their fellow countryman was living in a shelter, they came together and had a small fundraiser after which I was able to rent an apartment.

With the rest of the money, I set up a small curio stand in DC. I would get the things from Kenya: they’d send me kiondo’s and earrings and things like that and that’s what I did for nine years.”

Not one to miss an opportunity, he narrates how he learned to work the system so he wouldn’t have to rely solely on imports from Kenya.

“Sometimes I’d go to New York once a month, you could find earrings from China that looked like the ones from Kenya. I’d buy a dozen for 12 dollars and sell a pair for 10 dollars. I’d mix them up with the ones in Kenya which made things easier for me because importing from Kenya was expensive.”

Eventually, as it always does, life came full circle and Munene came back to Kenya lifetimes wiser to start his business. However, he was quick to clarify that the homelessness that he had to battle and grapple was not a lone occurrence but rather an open secret among many nationals who seek their fortunes in the US.

“Kenyans are homeless, you go to places especially in Baltimore and you find a big group of Kenyans who are homeless. They live in abandoned buildings. They light fires in the wintertime to ward off the cold.

In DC, I met people who’ve been there since the Tom Mboya Airlift: old men, people who’ve been there for a very long time. There was an ageing Luo I met, he was hungry most of the time. It [homelessness] is a very difficult thing.”

I ask him why they stay, why they wouldn’t just come back home. He explains that for them, it is difficult to return with empty hands from a land where they are expected to draw the milk and the honey.

“I have a friend there [in the US], the brother of a former Cabinet minister. The guy was homeless then, yet they are well up in Kenya. He doesn’t go back home because they’d ask him what he’s been doing. He has degrees, he has a masters from there.”

With a clarity sharpened by experience, he explains the situation, “They have that fear, to go back home with nothing to show.”

Munene is perhaps luckier than most. While he was able to return, those he has left behind can no longer be covered with the muslin cloth that we have weaved with our fantasies of America, the promised land.

Yet, these Kenyans on the streets of Baltimore, of DC, of Atlanta have homes. Maybe what bars the door are the locks of our own expectations, the expectations we place on the heads of those who leave like a crown.

“It takes a lot of courage to come back,” says Munene, a statement that bears more gravity than we should allow it.

By

Source-kenyans.co.ke

Below find some property that Munene is selling and call him:

Munene’s phone number: 0701521826. Email: Mosesmunene93@gmail.com

Homeless Diaspora: Dark Secrets of Kenyans in the US